Digging Up the History of My Immigrant Family

The search for my great-uncle who died in the coal mines of Southeast Kansas.

This summer I was feeling the urge to go on a road trip. After last summer’s trip to Slovenia, where the Dolinar family originally hails from (I wrote about it for my Substack), I wanted to chase down a lost piece of my personal history. Growing up, I was told the story of my relative Antonio Dolinar who was the first to come to this country and had tragically died in the coal mines. I wanted to try to find his grave.

Where was Antonio buried? Was he left in the coal mine? Was he given a proper burial? I wanted to go on an exploratory mission to find out.

In 1910, Antonio took a passenger ship across the Atlantic Ocean, probably entered the United States through Ellis Island, and rode trains all the way to Southeast Kansas. Why he left Slovenia is unknown. How he ended up in Kansas is also a mystery.

Antonio went to work in the coal mines, being paid in company “scrip,” living in a mining camp, and shopping at the company store. Even after the mining company took the reductions for his boarding and tools, Antonio saved up enough money to send for his brother Frank who is my great-grandfather. Frank made the trip across the Big Pond in 1911 and joined his brother working in the coal mines.

Frank then sent for his wife Antonia a year later. They raised three children — Stanley (my grandpa), Emma, and Frank, Jr.. I set out on a road trip to see what I could find around the city of Pittsburg (without an “h”) in Southeast Kansas.

At the current moment when we are hearing daily reports of immigrants being abducted by ICE — Trump’s secret goon squad — it feels like a good time to delve into my own immigrant past. Maybe it will encourage others to do the same. Perhaps this can give us some perspective on fighting the current white supremacist backlash.

I started by doing what I could with a few phone calls. In looking through my file of Dolinar family history, I came across mention of a cemetery in Yale, Kansas where Antonio was supposedly buried. I looked online for cemeteries in the area and found the Sacred Heart Catholic Church in the town of Frontenac. I called a number and got Suzy Wiley on the phone.

Death of an Infant

Suzy had no records of Antonio, but she did find a couple interesting new pieces of the Dolinar family puzzle. She located in the death records mention of an infant child who died on May 4, 1916 at only 17 days old. It was the child of Frank and Antonia, my great-grandparents. The death record lists the name of the mother. The baby was buried two days later in the Catholic church’s cemetery, called Mount Carmel Cemetery. A Catholic priest presided over the funeral.

Slovenia is a majority Catholic country, and apparently the Dolinars were Catholic, at least for a time before they assimilated to Protestantism.

It’s unclear from the records whether the baby was a boy or a girl. My aunt Diana, who is the family historian, heard the story about a daughter who died at a very young age. She was told the baby died while Antonia was at sea traveling across the ocean by herself to be reunited with her future husband. (How the child was conceived when they were apart for a year was a mystery to me.) My aunt Emma said she was named after the child.

Another newspaper article states an “infant son” died at the family home in Gross, Kansas, the company town where the Dolinars lived. Were there two Dolinar children who died at an early age? Did these two stories get combined into one?

Children were buried in a separate part of the Mount Carmel Cemetery, Suzy told me, with wooden markers, which had been burned during a fire. There was nothing to indicate where the young child was buried.

As I found out, Catholics are good at record keeping.

Suzy also discovered that my uncle Frank — Frank Dolinar, Jr. — was baptized at the Sacred Heart church. My uncle Frank was Catholic too.

Yet Suzy could find no records for Antonio Dolinar. If I wanted to learn more, she suggested I call Seth Nutt, director of the newly built Frontenac Public Library.

A. Dolinar

Seth had almost single-handedly led the effort, with the help of a small group of colleagues, to build the Frontenac Public Library and miner’s museum. It is soon to open in Frontenac. Talking to Seth over the phone, I told him about the search for Antonio, my lost great-uncle. He was able to find a newspaper mentioning that “A. Dolinar” had died on the morning of November 11, 1912. It was the first time I found the date of his death. The article stated he was working in Mine No. 13 of the Western Coal and Mining Company in the town of Yale when he was “instantly killed… by a fall of rock.”

Yet there was no cemetery in Yale, Seth said, to my dismay. After looking through more records for an Antonio Dolinar, Seth concluded, “I can’t figure out where he’s at.”

I told him I was hoping to come to Kansas to dig up my family history. He invited me to the library to talk with him and get a tour of the museum. He also kindly offered to drive me out to Mine No. 13 where Antonio was killed.

Detour Down Florissant

I packed up my Volkswagen Jetta and set out for Southeast Kansas. I stopped in St. Louis to see my aunt Diana. She said she had a family heirloom she wanted to gift me — a pipe from her grandpa.

While passing through St. Louis, I planned to meet my new friend Miles Pearson who is spending his summer in the city organizing Amazon workers. They were having a barbeque in the park and he told me I was welcome to come. Miles lives in Springfield, Missouri, where he is doing solidarity work at the Greene County jail. There, the sheriff is holding people for ICE. I recently interviewed Miles for my project documenting ICE jails and prisons in the Midwest. He told me about the Southern Missouri Immigration Alliance that he was helping to organize.

Pulling off the highway in St. Louis, I took a detour down Florissant Avenue, the street made famous by Mike Brown, the 18-year-old Black youth killed by a cop in Ferguson on August 9, 2014. It’s been more than a decade, but it feels like yesterday. I stopped to take a photo of a mural of Mike Brown on the side of a building off of Union Street at the intersection with Cote Street.

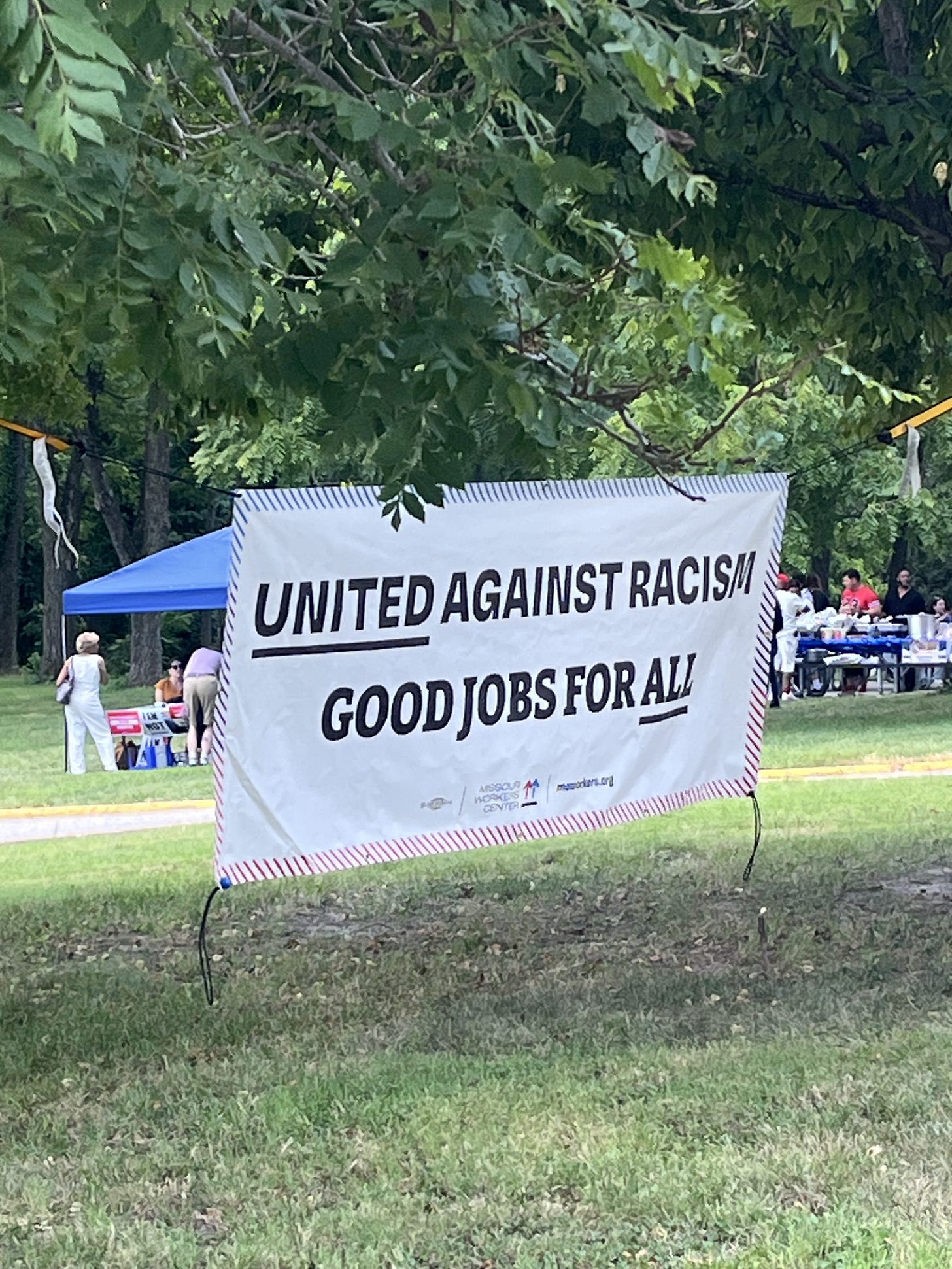

As I drove up to the barbeque, I saw a large banner that read, “United Against Racism, Good Jobs for All.”

I got there just in time to hear speeches by undocumented workers who gave powerful testimonies of what conditions are like under Trump’s anti-immigrant crackdown. One woman from Central America talked about how her manager threatened to call ICE on workers who were organizing. It was a stark reminder that Trump’s campaign is not just a white nationalist crusade, but an attempt to keep workers in their place. Racial capitalism needs a constant pool of cheap labor.

The speeches ended with everyone chanting, “When we fight, we win!”

Next, I joined my aunt Diana and her husband Robert at their home in St. Charles, on the west side of St. Louis. After dinner, we sat down in the living room, and she unwrapped a package with the pipe she wanted to pass on to me. Given to Frank Dolinar during his service in the Austrian army [Slovenia was once a part of the Austrian Empire], it is a porcelain pipe with ornate painting and a long stem made of cherry wood. It’s a beautiful antique.

Diana had surmised the pipe must be worth thousands of dollars, so she took it to an antique dealer. Much to her disappointment, she found out it was quite common. It was a pipe given to all soldiers in the Austrian army. It was maybe worth a couple hundred dollars. This story sounded more true. My great-grandfather was a coal miner, and a foot soldier, just an ordinary worker. I wrapped up the pipe and took it with me.

Entering Coal Country

When I crossed the border leaving Missouri and entering into Kansas, I noticed wind turbines in the distance. A century later, wind power had replaced coal power. The wind is always blowing across the plains of the Midwest.

My first stop getting off the road was at the Garden of Memories cemetery where my great-grandparents Frank and Antonia are buried. My uncle Frank is also interred there.

After finding the headstones for Frank and Antonia, I sat down and made an offering. I unwrapped the pipe, filled it with tobacco, lit it, and breathed in the smoke. I imagined the pipe was one of Frank’s few prized possessions he brought with him on his journey to the United States. I exhaled with gratitude for my immigrant relatives who made the long trip, dug coal from deep beneath the earth, and raised a family.

I checked into my hotel, the cleanest cheap hotel I’ve stayed at in a while. The owner was from India. I asked him about recommendations for dinner, but because he was vegetarian and there were no Indian restaurants in town, he had little advice. He told me he came here 14 years ago to run this hotel. He keeps a garden out back which I imagine is a little piece of paradise for what must otherwise be a lonely existence.

A Sister Dolinar

The next morning, I met Seth at the new Frontenac library, an impressive public library with enlarged photos of the town’s mining history on the interior walls. He invited me into his office, we shook hands, and sat down. He gave me copies of the newspaper articles he had printed out. He also showed me another newspaper that mentions the marriage of Appolonia Dolinar to John Homee (elsewhere spelled Homer), on July 3, 1907 in Yale, Kansas.

This is the first record indicating that a sister, Appolonia, was actually the first Dolinar to come to the country, before Antonio came in 1910. It betrayed my understanding of men who travelled far distances for work. There was a significant Slovenian community in Southeast Kansas and family came over one-by-one in a pattern of what is known as “chain migration.”

Seth gave me a tour of the mining museum he had put together. He had photos of the so-called “Amazon Army” of women who famously went out during a strike in 1920-21 and threw red pepper flakes at scabs coming to take the place of striking mine workers. He also had photos of Mother Jones, who visited the area, and Alex Howat, leader of the local chapter of the United Mine Workers.

I showed Seth photos from my own collection, including photos of my great-grandmother Antonia, who was one of the Amazon Women. He offered to include them in the museum display. He also suggested I reach out to Linda O’Nelio Knoll, the local expert on the Amazon Army, and gave me her phone number.

Visit to Mine No. 13

I was anxious to visit Mine No. 13. Seth generously offered to drive me in his pickup truck. I sat in the passenger seat as we continued our conversation. He pointed to mounds covered by overgrown vegetation where mines used to exist. In 1914, Southeast Kansas supplied the nation with one-third of its coal.

When we got out to the Yale crossing, Seth pointed out into the distance where Mine No. 13 once existed. Like other mine shafts, it was located next to train tracks that delivered the extracted coal north to Topeka or Kansas City.

Seth told me the historians he had talked to said the company “always retrieved” the bodies from mining accidents. He speculated that if a miner was too poor and had no family who could pay for a proper funeral, he may have been buried in a mass grave. He said mass graves were “common.” My heart sank to think Antonio could have been buried in an unmarked grave with other dead miners.

In 1888, there was a mine explosion at Mine No. 2 in Frontenac where 49 miners were killed. A plaque at the miners’ memorial next to the Frontenac library describes it as a major tragic occurrence and the greatest loss of life in the history of mining in Kansas. Several of the miners were buried in a mass grave, Seth explained to me.

Next, we drove through the Frontenac city cemetery. Seth pointed to an empty patch at the back of the lot with no head stones. That was the place where it was believed there was a mass burial of deceased mine workers.

It was almost too much to bear knowing. I was prepared to find no answers. But I was not ready to hear this could have been Antonio’s fate.

Another newspaper article we found says that two months later a judge in Girard, Kansas ruled in favor of $1,250 in damages to the next of kin of Antonio Dolinar.

It’s no replacement for the loss of life, but the family did get a token amount of money, what is today equivalent to about $43,000. Of course, it was just the cost of doing business for the Western Coal and Mining Company who made millions exploiting immigrant workers to extract coal from the earth.

The Amazon Army

The next morning, I met up with Linda O’Nelio Knoll, who has tried to bring recognition to the Amazon Army, given talks around the state, and written a play about the women. She started the website An Army of Amazons. Her grandmother Maggie Bellezza O’Nelio was one of the women who participated in the strike at the age of 23 years old.

I told Linda how I grew up hearing about the Amazon Army and that my great-grandmother was one of the women who went out to throw pepper at the scabs. She said my great-grandmother was one of 3,000-6,000 women who joined in solidarity with the striking miners. They did this before telephones or computers, with their own informal communication networks.

We met at the Pittsburg library. Linda wanted to show me a mural she helped to create of the women leading a march. We took a photo in front of the mural together, two descendants of the Amazon Women.

As I was driving home through Illinois, I took a different route on Highway 55 and passed the city of Mt. Olive where I knew Mother Jones was buried. I turned around and headed down some two-lane roads to find the Union Miners Cemetery on the outskirts of town. Known as a the “Miners’ Angel,” Mother Jones wanted to be placed to rest alongside miners who lost their lives in what is known as the “Battle of Virden” on October 12, 1897. A plaque quoted Mother Jones who said, “They are responsible for Illinois being the best organized labor State in America.”

Lost and Found

I got home rejuvenated and feeling a greater sense of rootedness to my past. Yet I was still left uneasy not knowing what happened to my great-uncle Antonio.

Wanting to leave no stone unturned, I reached out to Jerry Lomsheck at the Miners Hall Museum in Franklin, just north of Frontenac. Linda had told me to try them. I got Jerry on the phone and told him about my mission to find my great-uncle. He said he would do some research and get back to me.

A week later, Jerry sent me an email that began, “We found it!!” He included a copy of the death certificate for “Anton” Dolinar, which confirmed the date of his death, November 11, 1912, at the age of 29 years old. The cause of death was, “Killed by falling rock by mine, dead when found.” It also clearly states that he was buried at Mt. Carmel Cemetery in Frontenac.

I excitedly called Suzy to tell her the news. Yet she said she still couldn’t find Antonio’s name in her list of gravesites. She asked a groundskeeper to walk through the cemetery. The groundskeeper did not find the name, but he did find an empty patch of grass in the cemetery for the years of the 1910s. There were markers for the years before and after, but there was a gap in the dates. During those in-between years, Suzy again explained to me, they used wooden markers which had been destroyed by a fire. Antonio was buried in the same cemetery as the Dolinar child who died at 17 days.

In the end, this is not simply a story of discovery — not the kind we like to hear. This is a tale of hard times. It’s what previous generations of immigrants faced. In the midst of Trump’s anti-immigrant crusade, it’s a reminder of the abuse and exploitation that immigrants still endure today. It’s a sign that history is not a straight line, it’s a broken record.

Great story, Brian. I have very similar immigrant mining family history here in Illinois, same time period of arrival.

Loved this. You really showed your historian's drive for truth here. Amazing work and so nicely written. (and suspenseful)