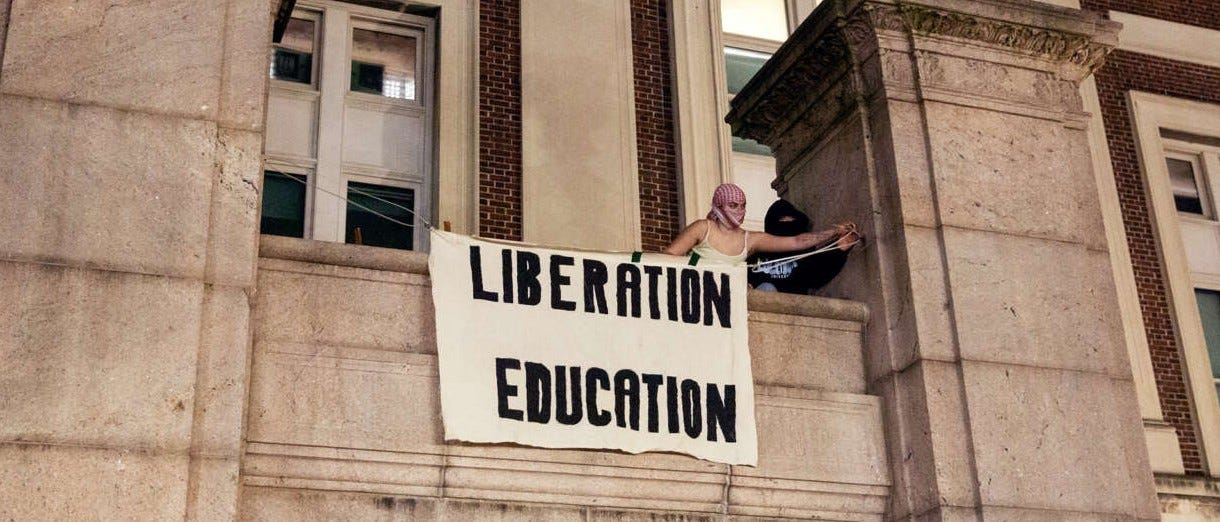

My latest article, “Campus Police Are Using Israeli Spy Tech to Crack Down on Student Protest,” examines the connections between the growing militarization of campus police, as witnessed during last year’s pro-Gaza encampments at the University of Illinois, and Cellebrite — the Israeli-based phone hacking company coming under increased scrutiny by activists.

It was written with Tara Goodarzi, a University of Illinois graduate, progressive attorney in Chicago, and my new friend. Following the encampment protests, Tara formed UIUC Alumni for Justice in Palestine. I reached out to her after I saw an article she published in Truthout, “Illinois Students Who Protested Gaza Genocide Are Facing Felony Mob Charges.” We first met over Zoom, but we had a chance to sit down at a coffee shop in Lincoln Park in Chicago. It was fun working with a co-author. I learned a lot working with Tara, whose family is from Iran. Her insights and expertise made for a powerful article.

The piece is also a follow up from a previous Substack article I wrote about the mob action charges against demonstrators.

I obtained the police reports on several activists charged with mob action from another friend and fellow local journalist Johnathan Hettinger, who FOIA’d the first police reports and kindly shared them with me. I followed up by filing FOIAs for police reports on the rest of the nine activists charged. After reading the documents, I was shocked by the degree of surveillance police had conducted on students. Police pulled images from the social media accounts of activists, followed their cars with license plate readers, and sent photos to a “fusion center” in Chicago to identify them.

Meanwhile, I had local activists reach out to me to file a FOIA for the university contracts with Cellebrite, who I’d never heard of before, but is a high-tech company based in Israel that develops software that can hack into cell phones. As my techie friend told me, so long as Cellebrite hackers can find “vulnerabilities” in our phones, our personal information and sense of security is threatened.

Subsequent FOIAs found that Urbana and Champaign police also have contracts with Cellebrite. Around the same time, Grace Wilken and Jaya Kolisetty introduced a police surveillance ordinance in Urbana that started to get some traction. I spoke before Urbana city council highlighting the human rights abuses documented by governments using Cellebrite technology to spy on journalists and activists. My friends at the CU Muslim Action Committee released a statement about Cellebrite contracts in Champaign where they have been lobbying to get the city to divest in Israeli companies.

As this ordinance was moving forward, a drama was unfolding over who would be the next Mayor of Urbana. I sat down for dinner with DeShawn Williams almost two years ago and he shared with me his plan to run for Mayor. Not long after, the Old White Guard in Urbana led by Mayor Diane Marlin, the current mayor, found candidates to run against DeShawn, Grace Wilken, and Chris Evens, my long-time friend and the alderman most critical of the police (Chris is also my representative in District 2).

The vote on February 25, 2025 would be a mandate on police accountability.

Just before the election, there was a weekend of murders, including the tragic death of a 7-year-old in east Urbana. The pro-police side, including the police chief, tried to use this as an opportunity to argue for more police. It was a test for Urbana.

Last night, all three candidates — DeShawn, Grace, and Chris — won their races. DeShawn is the first African American Mayor elected in Urbana. The election showed that candidates can run on police accountability and win.

Surveillance in a Box

After growing public pressure, on Monday night, February 17, 2025, Urbana police deputy chief Dave Smysor, along with digital forensic investigator Andrew Rapolevich, gave a presentation to city council about Cellebrite. Claims about Cellebrite, Smysor said, had not been “accurate” and he wanted to “put us on the same playing field.”

Smysor tried to assuage community concerns in front of council. He claimed all of Urbana police’s surveillance equipment, “I can fit in a cardboard box.” He brought his own box to prove the point. It contained a set of binoculars and a “Vietnam-era scope.” These things sit “in a closet,” he said.

Council member Grace Wilken asked why Cellebrite was not included requests about equipment in relevance to the ordinance on surveillance technology.

Cellebrite is an “investigative tool,” Smysor told council with a straight face, “not a surveillance tool.”

Grace pointed out that the original definitions in the ordinance referred to “software/hardware relating to access to a mobile device.” Smysor thought it didn’t apply.

This was the same talking point we got when Tara and I asked a university spokesperson about Cellebrite. They said campus police do “not use Cellebrite technology for surveillance.”

We will have to wait to see if Urbana city council, with a new mayor, will pass the police surveillance ordinance. DeShawn has said he favors the ordinance.

Stay tuned, for my next Substack I’ll discuss more police surveillance from my investigation into the University of Illinois’ fleet of drones.

Congrats to Mayor DeShawn! Congrats to Urbana!

Thanks for staying on top of these issues and reporting same.